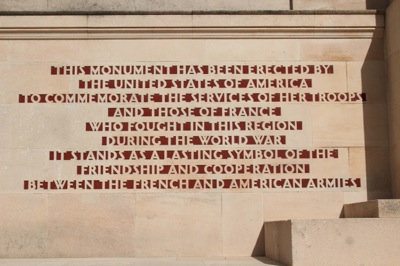

The summer holiday is a perfect time to explore one’s area and discover new places. As this region is famous for the numerous and significant battles that were fought during World war One, a number of memorials have been erected as a tribute to the soldiers who crossed seas and oceans to fight for our freedom.

The American Memorial in Château-Thierry is an impressive monument situated upon a hill near the town of Château-Thierry. It offers a wide view of the valley of the Marne River and is located about 54 miles (87 km) east of Paris. It was designed by Paul Philippe Cret and built in the 1930s. It is managed by the American Battle Monuments Commission.

It commemorates the achievements of the United States forces that fought in the region during World War One when in 1918, the 2nd and 3rd United States Infantry Divisions took part in heavy fighting around the area during the Second Battle of the Marne. The monument consists of an impressive double colonnade rising above a long terrace.

On its east facade, you can see the Great Eagle above a map showing American military operations in this region, an orientation table pointing out the significant battle sites as well as the names of the troops involved.

On its west facade are heroic sculptured figures representing the United States and France. Can you tell which is which?